AM / FM? NOPE...

I WAS BORN TO USE SSB

When do YOU think Single-Sideband was first introduced?

(Don’t worry—this isn’t a test, and you won’t be graded. If it were, I’d have flunked too.)

Well, the answer might surprise you: 1918, by AT&T engineers!

Whipping out my Mr. Peabody calculator, that means it was introduced 107 years ago. I never would’ve guessed it happened so early in the world of communications.

I think I first read about it in the book Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio. It’s an excellent deep dive into the discoveries, patents, lawsuits, and the brilliant (and sometimes combative) men who shaped radio history. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it. While the book isn’t entirely about two-way communications, it definitely “colors the background” and gives a broader context for how the wireless revolution came to be.

The book was also adapted into a PBS documentary of the same name, narrated by Jason Robards. It runs about 100 minutes—not everything from the book made it in, but it’s still a great watch. I wouldn’t be surprised if you could dig it up on YouTube.

Now, back to SSB. It entered commercial service with transatlantic radiotelephone communications in 1928. Here are a few historical benchmarks:

-

1915: John Renshaw Carson filed the first U.S. patent application for SSB modulation.

-

1918: AT&T engineers conducted the first practical SSB transmissions, proving its efficiency in both bandwidth and power.

-

1927: SSB was used commercially for long-distance radiotelephone service, linking New York and London.

-

1930s: Telephone companies used SSB for frequency-division multiplexing (FDM), carrying multiple voice calls over a single line.

-

Post-WWII: Amateur radio operators began experimenting with SSB. By 1957, even the Strategic Air Command adopted it for long-distance voice comms.

Commercial SSB transmitters for the ham bands started showing up in the early 1950s, but they didn’t really catch on until the 1960s. Many hams were still using AM into the late ’50s.

Before that, CW (Morse code) ruled the bands, and when AM came along, some purists weren’t too thrilled. You’d hear things like “A real ham doesn’t use AM”—similar to what happened decades later when Morse code stopped being a requirement for licensing. I remember hearing plenty of QSOs back then where veteran hams grumbled that the new guys weren’t “real hams” because they didn’t have to pass a code test.

CBers had a different path. They didn’t have decades of tradition tied to one mode before switching. Sideband started trickling down to CB radios, first as DSB (Double Sideband), then as SSB. The biggest hurdle was the limitation of just 23 channels—trying to fit multiple modes into that space was tricky. Early on, there was a bit of snobbery too; some SSB operators looked down on those still using AM. And back then, SSB rigs weren’t cheap, adding a little "elite status" to owning one.

CB radios have come a long way since those early AM-only days, but for many of us, the magic has always been in Single Sideband.

I still remember the thrill of getting my first sideband radio—a Midland 13-880b—in 1971. At the time, Midland was a big name in the CB world. They offered two popular base stations: the 13-885, advertised at 15 watts, and the more budget-friendly 13-880b, at 10 watts.

To the untrained eye, they looked like twins, but inside, there were differences. The 13-880b may have been lower powered, but it was way more accessible for those of us who wanted in on the SSB experience without breaking the bank. Sure, the wattage difference didn’t even make a full S-unit on the meter, but around town, those extra watts gave you some serious bragging rights.

The shift from AM to SSB was a total game-changer for hobbyists and radio enthusiasts.

The clarifier was the secret sauce—it let you dial in someone’s voice with precision, even if they were slightly off-frequency. On AM, you’re locked into whatever frequency you’ve got. But SSB? That gave you control. It felt more professional, more refined.

Early SSB rigs were something special. The clarifier didn’t just affect what you were hearing—it shifted both transmit and receive. That meant when you tuned someone in, you were also shifting your own signal. You could find a quiet spot just off the main channel and hang there with your crew like your own private slice of the airwaves. (Of course, the FCC cracked down on that pretty quick.)

SSB gave you better range, less static, and a much cleaner signal overall. Combine that with the eerie coolness of hearing voices that sounded alien until you clarified them, and it wasn’t just radio—it was an experience. Lafayette Telsat 25A AM/SSB Base/Mobile

Were you into CB back in the day? Or just getting into HF now? Shoot me an email and tell me your story—click on WOODY here, or at the end of this article to drop me a line! I love reading stories about how you got into CB and/or Single-Sideband...

MIDLAND 13-880B, HENSHAWS 70.5 CATALOG, BACK PAGE

SSB and the Haunted Stereo: A CB Radio Tale

Single Sideband (SSB) had all kinds of quirks and unintended consequences—especially back in the analog days. One of the most iconic side effects? That legendary “Donald Duck” voice when someone on AM tried to listen to an SSB signal without a BFO (Beat Frequency Oscillator). To anyone not in the know, it must’ve sounded like absolute gibberish—like a duck squawking in some kind of secret code.

Take, for example, the dentist next door.

At one point, he started picking up my transmissions through his stereo speakers - and heard every word. Naturally, when I switched over to SSB mode, it gave me the perfect alibi. The audio was so garbled on his end that I could plausibly deny it was me. Imagine sitting down to relax, only to have your living room sound system suddenly possessed by a spectral duck speaking nonsense. He was probably thinking, "Why is my stereo haunted by a duck speaking in tongues?" and "Why does it always seem to disrupt Glen Campbell singing Wichita Lineman"?

“Must be someone else,” I’d say with a straight face, pointing the finger squarely at my CB nemesis—“The Bald Eagle.”

The Eagle lived less than 300 yards north of the dentist, running a Browning Mark III with an amplifier. Whenever he swung his PDL-II beam toward my direction, both my place and the dentist’s got lit up like Christmas trees. It wasn’t pretty.

Eventually, we threw some filters on the dentist’s equipment to block the RF bleed-through. But for a short time, I had the perfect cover.

Now, onto the technical side:

Why does SSB seem to have more power than AM on the same CB radio?

A fair question—after all, CB radios are legally capped at 4 watts for AM and 12 watts PEP for SSB. So how does it work?

Let’s break it down:

Each CB channel is a specific frequency assigned by the FCC. When you transmit in AM (Amplitude Modulation), your 4-watt signal is split into three parts:

-

The carrier (the central frequency),

-

The upper sideband, and

-

The lower sideband.

That 4 watts doesn’t go to one place—it’s distributed across all three components. So the actual energy in the voice-carrying sidebands is only a fraction of your total power.

Now enter SSB (Single Sideband). SSB removes the carrier and one of the sidebands, transmitting only one sideband—either upper or lower. This concentrates all the power into just one portion of the signal, making the transmission far more efficient.

Instead of dividing energy, you’re focusing it. Think of it like the difference between a flashlight (AM) and a laser pointer (SSB). Same general power source, but the laser gets a lot more bang per watt.

So even though you’re technically staying within legal limits—SSB allows up to 12 watts peak envelope power (PEP) for voice—you get clearer audio, longer range, and better penetration through noise, all because you’re not wasting energy on redundant signal components.

To simplify, I like to use my OREO cookie analogy..

Welcome to Channel 16 — your channel.

Now, think of it like an Oreo cookie.

That creamy white center? That’s your center slot — the sweet spot where your channel lives. The chocolate wafers on either side? Those are the upper and lower sidebands of your signal.

When you’re transmitting in AM (Amplitude Modulation), your 4-watt signal gets spread across the entire Oreo — both wafers and the center. It’s like trying to frost the whole cookie with just a dab of icing. It works, but the coverage is thin, and not as strong as it could be.

Now, switch over to SSB (Single Sideband) — either USB (Upper Sideband) or LSB (Lower Sideband) — and you’re getting smart. That same 4 watts is now concentrated on just one side of the Oreo. No more wasting power on the whole thing — you're putting your energy exactly where it counts.

That’s why AM radios list 4 watts, while SSB radios often show 12 watts PEP (Peak Envelope Power). SSB is more efficient, more focused, and gives you a stronger, clearer signal.

Bottom line?

SSB is your power play.

More range. More clarity. Less wasted energy.

REGENCY IMPERIAL DSB - REDUCED CARRIER BASE STATION WITH SSB RECEIVE

Double Sideband (DSB) modulation came about as an improvement over traditional AM (Amplitude Modulation), but it never really took off in a big way. One of its biggest downfalls was inefficiency—DSB transmitted both sidebands, which meant using up twice the bandwidth and more power than necessary. On top of that, many DSB systems ran with a reduced carrier, which, while slightly more efficient than full-carrier AM, still didn’t make it very practical. It was a small step forward, but not quite enough.

TRAM OFFERED A DSB MOBILE RADIO IN THE EARLY 60s - The Corsair

Back in the day, when I was young and dumb, and before I really understood what DSB was all about, I wanted one of those rigs badly. I could almost smell that fresh new-radio scent just thinking about powering one on. I remember flipping through a Tram catalog and seeing the AM-LSB-USB selector switch. I thought, "Hey, this must be an SSB rig!"—not realizing the limitations that came with DSB.

Single Sideband (SSB) modulation emerged as a solution to these problems by transmitting only one of the sidebands and eliminating the need for a strong carrier. This significantly improved both power and spectrum efficiency. As a result, DSB technology quickly became outdated, and SSB modulation became the preferred standard in radio communications.

SAME INNARDS, DIFFERENT LOOKS?

Enter Single Sideband (SSB). This modulation method fixed most of what DSB got wrong. By stripping away one of the sidebands and the carrier entirely, SSB drastically improved both power and spectrum efficiency. With less bandwidth used and more power concentrated into a single sideband, communications became clearer and more reliable over long distances. No surprise, then, that SSB quickly outpaced DSB and became the gold standard for serious radio operators around the world.

DSB might’ve seemed like a step toward progress, but it never quite clicked with the public. For instance, if you were transmitting on channel 17, AM transceivers could still hear you, since DSB did carry a (reduced) carrier signal. At the same time, SSB stations could also copy your transmission—whether they were tuned to LSB (Lower Sideband) or USB (Upper Sideband). But practically everyone used LSB back then, so if you flipped your mode selector to LSB, you could usually pick them up clearly.

In the end, DSB just wasn’t efficient enough to stick around. SSB took over the airwaves, and the rest is history.

I have a nice looking 350 on the display shelf, but I've never checked it out. Maybe it's time...

I bought the Viking 352 in January 1976 after I moved to Texas (1975), and I had a blast with it.

Nothing has come along to truly replace Single Sideband (SSB), and at this point, the number of transceivers on the air is nearly impossible to count—especially when you consider those "10-meter" export radios that can be easily modified to operate on 11 meters.

Another class of radio that deserves mention is the HF ham transceiver, which often comes with a 100-watt output. These rigs can't be ignored. While there's a legitimate reason to modify HF radios for MARS (Military Auxiliary Radio System) communications, the ease with which many of these radios can be opened up makes you wonder if the manufacturers don’t know exactly what they’re doing. They understand that a significant portion of their sales go directly to CB or freeband users, and frankly, that doesn’t bother me.

I'd much rather hear a clean signal from a modified HF rig than deal with the interference from a poorly designed 10/11 meter export radio that splatters across the band and makes communication nearly impossible, unless they were using quality FCC approved radios, like my current favorites: The President George and/or President McKinley, along with the legendary Cobra 138XLR and/or Uniden PC-122XL.

I was still chatting away on my Midland 13-880B, but I was starting to grow weary of the constant bleedover, a frustrating side effect of its weak adjacent channel rejection. One evening, while talking with one of the adults I regularly connected with on channel 16 LSB, he excitedly told me about his brand-new base station—a gleaming SBE Super Console. The moment he switched over to it, his audio quality went from decent to absolutely stellar. It was like flipping a switch from dusk to daylight.

Naturally, I had to know more.

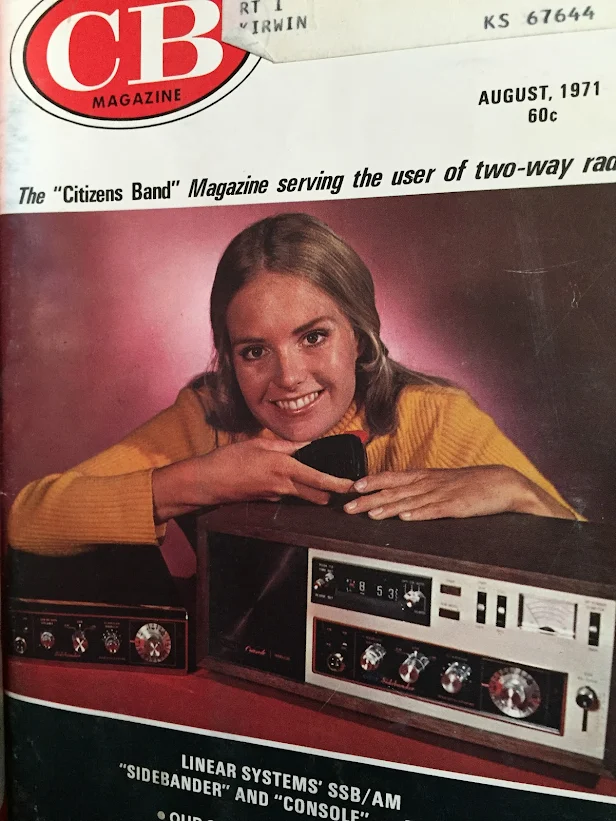

I grabbed the most recent CB radio buyer’s guide and started flipping through it eagerly, hoping to catch a glimpse of this audio marvel. But all I could find was the SBE “Sidebander,” a mobile unit—not what he was using. But a few days later, my monthly issue of CB MAGAZINE arrived with one on the cover Clearly, this called for an in-person investigation. We set a date for me to visit “Mister Chips” and check out this legendary rig for myself. I confirmed with my dad to make sure he was free to drive me (I was still a few years away from earning my license), and then came the hardest part: waiting.

Time dragged… and dragged… until Friday evening finally rolled around.

Mrs. Chips greeted us at the door and led us through the house into the kitchen. In the breakfast nook corner sat Mr. Chips at the table, grinning like a proud pilot in front of the biggest, most beautiful sideband base station I’d ever seen. The SBE Super Console wasn’t just a radio—it was a presence.

Just to give a little context—back in the '60s and early '70s, it was pretty common to find ham and CB setups right in the kitchen or breakfast nook. It wasn’t until the mid-’70s that gear started migrating into spare bedrooms or down to the basement. But at that time, that cozy corner of the kitchen might as well have been mission control.

IT TOOK DECADES BUT I FINALLY GOT ONE

Mr. Chips was eager to show me all the features this radio had to offer—especially the low-band police/fire scanner built into its right side. I could already picture it sitting proudly on the desk in my shack (bedroom). If his goal was to impress me, he definitely succeeded.

“Do you know what SBE stands for?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Sideband Engineers,” he exclaimed, clearly delighted to share this nugget of knowledge. He went on to explain that they also made ham radios. To Mr. Chips, that was a mark of high-quality gear—and he wasn’t wrong. During this tumultuous time in CB radio, the company was acquired by another firm, but they kept the SBE name, now rebranded as SBE, by Linear Systems. The box below still had "by SBE" on the box, shortly replaced with "by Linear Systems".

At the same time the Super Console was released, they also introduced a lower priced AM/SSB base called the SBE "Console". Basically it was the Super Console minus the scanner, as seen below.

We've established that the AM mode is wide, and being wide, it's prone to have more static and atmospheric noises compare to SSB. In my early days of sideband, it was common to hear a lot of cr@p almost covering up other stations, and when we went to LSB (lower sideband) there was far less noise, making it easier to have a QSO (conversation), and easier on the ears. The fact that the channel is split into thirds helped decrease the noise. I had a lot of fun on AM, with my Lafayette Comstat 23, but I found sideband to be "my cup of tea", and except for when I'm traveling and listening to channel 19, all of my radios power up on single-sideband. LSB for 80, 40, and 11 meters, and USB for just about everything else.

One odd aspect of 11m sideband using LSB is that Internationally, any station using sideband above 40m should use upper sideband, or USB. If you listen to the area between ch.40 and just below 10m (i.e. - Freeband), you find almost all non-U.S. stations using USB, especially on the triple nickel (27.555). I don't recall a mandate telling everyone to use LSB, but because it had a more pleasing sound to it versus USB, that everyone just hung out there until eventually, LSB became the de-facto mode for CB radio frequencies.

For as few of these (ARF-2001) that were made, they certainly appear on eBay more often than you'd think.

Back in the "Olden Days" CB RADIO was like a big guy who couldn't find a belt to fit him, so he wore suspenders. The "A" channels (3a, 7a, 11a, 15a, and 19a) were found in-between the 23 channel range, while 22a and 22b were actually frequencies above channel 23, and many stations were able to access these frequencies for the most part, many used them while in the SSB mode. After the FCC approved 17 new channels, Citizens Band Radio now had 40 legal channels, and frequencies below channel 1 and above channel 40 were self-ordained as the "Freeband", a vast wasteland of airspace with occasional visitors, and several hearty souls who planted their flag on a frequency, calling it their home channel. Frequencies above 40 almost exclusively used lower sideband, while International stations (following International standards) used USB. The frequencies below channel 1 adopted that space for either AM or FM modes.

I hope this wasn't too confusing - I was just trying to get you an overall view of how the modes came about, and their pluses and minuses. Sideband may not necessarily be the mode you'd choose, but it was for me. There are plenty of stations on AM, complete with glaring heterodynes, while on SSB we have the 111111111111111 station. Either way, try to make the best of it, and have a good time!

OTHER RELATED STUFF:

- CB DAZE - First SSB CB radio?

- What is sideband (wiki)?

- Ham radio school sideband explanation

- University of Hawaii - CB Sideband

- CB DAZE - The Times Were A Changing (to SSB)

- CB GAZETTE - (mostly) SSB CB REVIEWS

- ARCHIVED LIST - CB Magazine's Here & There

- ARRL Website

- BELLS CB RADIO HOMEPAGE

- DX Engineering - Website

- HRO - Ham Radio Outlet

- What is on the market? Best and worst SSB radios 10m and CB

- ON ALL BANDS - POWERPOLE HOW-TO

- DX ENGINEERING'S "ON ALL BANDS" Homepage

- THE BEST HAM/CB WEBSITE: Worldwide DX

- List of various frequencies

- The President McKinley: A decent SSB mobile

- The Moonraker Titan am/fm/ssb/cw review

- Henshaws 1974 Catalog (a.k.a. -our radio "Wish Book")

- Learn something about the man: Donald L. Stoner

- Book about the inside magic of AM-FM & Single-Sideband radio

- Radioshack catalogs

- This book about CB SSB by Tom Kneitel is a must have!

- Another great source for radio reviews - CB RADIO MAGAZINE

WHEN THIS ONE STARTED, I ALMOST THOUGHT I GOT IT MIXED UP WITH THE BEGINNING OF "THE OUTER LIMITS" CLIP ON YOUTUBE, THAT I SAVE IN THE SAME FOLDER...

UPDATE 05-21-2025:

I RAN ACROSS THIS VERY INTERESTING VIDEO THAT CAME OUT A FEW DAYS AGO (MAY 18th). The subject matter fit nicely into this subject, and I hope you enjoy watching it as well!

Okay, I'll stop here because even I'm overwhelmed. Perhaps this should have been a multi-part Blog post, but it is what it is, and I hope the stuff I left out was the "Right Stuff". 'Nuff Said...

73

PS – Some Operators Just Gotta Argue...

Spend enough time on the air, and you’ll run into them: operators who just have to disagree — about everything. Whether it’s equipment, operating modes, or which radio service reigns supreme, they’ll make sure their opinion gets across loud and clear.

Here are a few of the most common gripes and one-upmanship lines I’ve heard over the years:

-

“Hams are smarter than CBers.” (Because apparently memorizing multiple-choice questions is the mark of genius.)

-

You say, “What a beautiful day,” and they snap back, “No it isn’t.”

-

“CW is the one true mode.” And if you haven’t mastered Morse code, you’re not really a ham.

-

“Hams respect each other more than CBers do.”

-

“The best capacitor for a magnetic loop?” Easy — a flux capacitor. (Thanks, Doc.)

-

“CBers are the Kias of the airwaves. Hams? We’re the Cadillacs.”

-

And the old “radio service ranking” argument:

-

Ham radio

-

GMRS

-

MURS

-

FRS

-

CB

-

And let’s not forget the endless mode wars. Depending on who’s talking, the “best” mode shifts like the weather:

-

Sideband

-

CW

-

Digital

-

AM

-

FM

FM is a mixed bag when it come to ham repeaters, even though it’s been widely used and accepted, for the most part everyone is civil enough to each other, while other repeaters in the same, or other areas aren't up to what it takes to maintain keeping morons in check (think of some 80m frequencies or 7.200 40 meter conversations. CB in the UK: In fact, FM was the only legal CB mode in the UK until SSB became approved sometime after 2010. In the U.S., FM was occasionally heard on non-standard CB frequencies like 26.805 — far enough below channel 1 (26.965) that you’d need an export or modified ham rig to reach it.

GMRS: The Rise of Off-Road Radio

GMRS has exploded in popularity — especially among off-road groups. In some cases, users stretch the rules a bit, depending on the crowd. A lot of ham areas rarely have a surplus of open air time with their repeaters and active FM users, while others feel like ghost towns on those same frequencies. GMRS repeaters can be hit-or-miss as well.

Interestingly, GMRS handhelds look and feel like high-quality ham HTs, with solid features and rugged designs. Marketing and media have definitely helped the service grow, but the mobile/base units? Some of them look like props from a retro Sci-Fi show. Maybe that’s part of the appeal — or the disconnect. Those HTs clipped to belts in Jeep caravans might be great for the trail, but they’re not everyone's cup of tea.

Personally, I rarely if-at-all use UHF, in general sticking to VHF SSB. I keep a few GMRS HTs around for disaster readiness, but the only use they get is usually a once-a-month on-the-air check to make sure nothing has gone wrong.

My Personal Take

When it comes to radio, everyone’s got their preferences — kind of like standing at the gas station beer cooler, reaching for your favorite brew while someone else grabs theirs.

As for me:

-

Ham & CB radio are tied for #1, and I love using both services. CB radio licensing is free, while ham and GMRS cost $35.

-

Anything and everything else falls below them.

But hey — that’s just how I see it.

73 from this side of the mic.

No comments:

Post a Comment